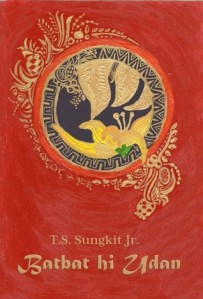

Published 2009. Author, Telesforo S. Sungkit, Jr. Central Book Supply Inc.: Quezon City. 215 pages. Finalist, 2010 Madrigal-Gonzales Best First Book Award.

Set in a land still untouched by foreign invaders and told in a powerful mixture of Tagalog and Binukid (the author’s mother tongue), Batbat hi Udan pulsates with what our contemporary literature lacks: rootedness in our precolonial past. At the very least, it provides a glimpse of how our ancestors understood and grappled with their world.

The novel is an intricate web of adventure, violence, romance, treachery, sacrifice, and love of banuwa — all woven in a world shared by humans and supernatural creatures and depicted through a cogent blend of magic and realism. Embedded in its plot is a recounting of why Mindanao is not hit by typhoons , why the balete tree is inhabited by alagasis (giants), and other legends etched in the Filipino psyche.

Novelist and poet Edgar Samar says that Batbat hi Udan, although written in prose form, is marked with the “classic narrative rendering of an epic”. But more than a mnemonic device, as Samar asserts, parallelism is used in the epic not only for aural adornment to aid memory but also for making description more forceful and vivid. For instance, the author seals off most battle scenes with the following repetition : Pingkian ng talim sa talim. Ng talim sa kalasag. Ng kalasag sa kalasag. Such kind of rendering, with which the whole opus is fashioned, does not only attest the author’s story-telling prowess; it also raises the novel to the level of fine poetry.

Batbat hi Udan revolves around the life and exploits of the central character Udan, a young man from Hanapulon who frees his people from the clout of the evil Kalibato, Tium hu Gaun, and other malevolent tagbayas. In the course of his journey, Udan – brave and adept in battle — has earned the respect and admiration even of his enemies who can’t help but marvel at how swift he swirls and how strong he strikes.

Udan’s adventure starts when his father, Datu Maghusay, tells him to join Datu Manlidasan’s caravan in carrying manggad (dowry) to Impasug-ong. Excited about the idea of “getting a whiff of air from the other side of the mountain and setting foot on foreign land”, Udan goes with the troop.

Little does he know that such journey will lead him, his tribe Hanapulon, and its neighboring banuwas – Lantapan, Yandang, Kimambong, Dalwangan, Impasug-ong, and Sumilaw – into the vortex of pangayaws (tribal wars), a series of battle that will take the lives of almost all his loved ones.

On their route to Impasug-ong, Udan loses his way and finds himself alone in a secret passage that leads to Lidasan, a world most of his kins believe exists only in the imagination. But Lidasan is real. Here Udan encounters creatures of various kinds — aligasis, bakesans, tagbusaws, mantianaks, and so many others that devour human flesh to exist. In Lidasan, Udan suffers great misfortunes and faces death eye to eye.

Lidasan, however, is also the place of Udan’s transformation. It is here where he attains his full human potential and realizes his power and prime responsibility as bagani. It is here where he discovers his place in the grand design of life’s cycle of destruction and rebirth. A fate that destines every human to obey.

It is in Lidasan where he meets Hapoy ha Tagkalegdeg, Bolak ha Mahumot (Blazing Flame, Fragrant Flower) or Ananaw — also an adept bagani — with whom he falls in love. With whom he experiences the bliss of losing innocence.

In his final encounter against the fiercest of his foes – Tium hu Gaun, the wind whispers to Udan that he faces an enemy much stronger than he is; therefore, he must perform the saut (war dance). He knows that the message comes from the same tagbaya that helped him defeat the first alagasis (giants) he fought.

But he already understands, now that he knows what befell his forebears when they accepted Tium hu Gaun’s help. Unlike them, he won’t pawn his heart and liver for a power he knows he himself possesses and can muster.

And Udan refuses to perform the saut: Bakit ako magsasaut? Sinasabi mo bang hindi ko kayang pumaslang ng tagbaya? Enraged by such irreverence, the tagbaya summons a great whirlwind in its attempt to subdue the bagani. But Udan has already attained his full humanity. Sapagkat ang lahat ng nananahan sa kaniyang katawan ay naging iisa. (Because everything that resides in his body have united and become one) .

Udan swirls and fuses with the whirlwind. When the wind settles, the tagbaya is seen kneeling, pleading the bagani to kill him as deserved by a vanquished. But the bagani does not oblige. Instead, he orders the tagbaya to drift away with the breath of trees and gain strength. He commands the tagbaya to guard the land of his ancestors against typhoons.

Then he swings his kampilan towards Tium hu Gaun. As its head rolls, sparks of light flash like lightning and thick black smoke envelops the surrounding. When the smoke disappears, the livers and hearts of all the humans eaten by Tium hu Gaun lay scattered all over the place. Beside each pair of liver and heart floats the gimokod (soul) of their owner. With this final act, Udan frees his ancestry from the curse of indebtedness to the most powerful tium and fulfills his destiny as the greatest bagani of his people.

Batbat hi Udan is written by a lumad of Higaonon tribe, the first writer from Bukidnon to pen a literary piece of this kind. The author himself says that the novel is a Philippine version of The Lord of the Rings .

Perhaps. But it surely is more than that masterpiece. Because the events told in Batbat hi Udan are part of our almost forgotten past, our very own stories vivified by the masterful rendering of Telesforo Sungkit, Jr.